‘Like Lego for grown-ups’

Austrian entrepreneur Hubert Rhomberg wants to revolutionise one of the last workplaces that digitisation has so far passed by – the building site – using good old-fashioned wood

Hubert Rhomberg on the roof of the firm's headquarters

• Hubert Rhomberg has set himself a big challenge: to create the biggest construction firm in the world by breaking with tradition. He is not looking for bricklayers or foremen but for software developers and light designers. He wants assemblers rather than builders, and he wants them to create multi-storey tower blocks – from wood.

This fourth-generation master builder took over his family’s construction firm, Rhomberg Group, the fifth largest in Austria, in 2002 and promptly co-founded a competitor company, Cree, to challenge the life’s work of his forebears. “We didn’t know it couldn’t be done, so we did it,” is a typical quip as he welcomes visitors to his offices in Bregenz, on Lake Constance. Another of his dictums is: “No one knows singly as much as we all know together.”

The experts said building timber-framed tower blocks was impossible. But Rhomberg has done it. They are prefabricated in sections in his factory and only have to be put together on site. Assembly is quick, quiet and clean; it takes a handful of workers a few weeks. They are not actually building, just putting things together – like Lego for grown-ups. Individual sections of the building can be assembled in different ways for various uses. There are no light switches as this is controlled by computer, mobile or voice. The lights feed back data on room temperature or humidity and can be linked to artificial intelligence devices.

Rhomberg is convinced that his smart hybrid high-rise buildings, in which only the foundations and stairways are concrete, will stand tall for several hundred years. The software is updated every few months. The code for each building is stored on an online platform so it can be reproduced or developed anywhere in the world. Cree is pushing ahead with “construction 4.0”.

Rhomberg was 27 when his father asked who would be carrying on the family firm. His elder brother was not interested, but Hubert agreed. He served three years in “apprenticeship” with a leading Austrian competitor, Strabag, and came back a real workhorse, he says. His father then put him in charge of Rhomberg’s civil engineering division, where he developed railway technology. Today Rhomberg says he learned from his father how to negotiate, and from his mother a love and awareness of nature.

Work in progress in the company’s subsidiary, Sohm HolzBautechnik

Stay clean

Guilt about sustainability goes with the territory for many modern builders. “In concrete alone there are often hundreds of potentially toxic substances. The construction industry is responsible for 40% of all harmful climate gases and global refuse, and 60% of freight transported by road,” says Rhomberg. “Whole beaches are dug up in Australia to be transported across the world just to make cement for high-rises.” Today’s new-builds will be seen as bulky hazardous waste by our grandchildren, he believes.

So, is there another way? In 2010, Rhomberg and René Benko, head of Signa Holding – Austria’s biggest real-estate investor and owner of the Karstadt chain of department stores – set up Cree, a small timber construction firm. Richard Morscher, who owns an advertising firm, was also on board. Two years later, the firm completed the award-winning eight-storey LifeCycle Tower in Dornbirn, south of Bregenz. Designed by the architect Hermann Kaufmann, it was the first medium-rise building to be constructed in timber.

It was the prototype for the concept of building towers with prefabricated timber modules, and it still attracts several thousand visitors every year. Of course, fire regulations posed one of the biggest challenges. “In our lab tests we were able to prove that wood can meet safety requirements very well,” says Rhomberg. Assembling the factory-built wooden sections took just eight days.

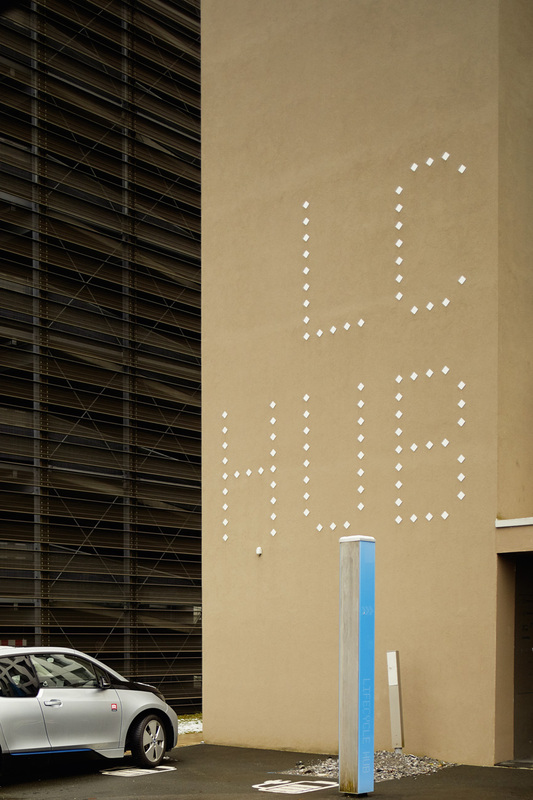

The impressive headquarters of Cree

Attacking the world’s biggest industry

Timber skyscrapers are now planned or under construction in several cities. The biggest so far is due to be finished in the Aspern quarter of Vienna in 2018. In Delhi, French architects are planning another six high-rises and there are plans for a 300-metre high wooden tower block in central London, the 80-storey Oakwood Tower at the Barbican. Cree has already finished an eight-storey house in Montafon in Austria, and is developing new projects in Berlin, Hamburg and Singapore.

There are obvious advantages over concrete: construction time is slashed. Construction is quieter and cleaner. It is more environmentally sustainable. According to Cree, each building will generate less than 1,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide over its lifetime, instead of 10,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide. In addition, every building application contains a full list of materials used, along with instructions for dismantling it again.

The construction industry has a global turnover of about $10 trillion (£7.5tn). It accounts for about 9% of the gross domestic product of the European Union. Yet for decades it has hardly changed. Most smaller buildings in Europe are still built with bricks and mortar, then plastered and painted. In the bathroom or kitchen, wall and floor tiles are stuck on and the joints grouted. Plumbers make holes to connect up to the water supply and cover them again from the outside. Sub-contractors employ other sub-contractors: all sorts of trades are interacting and they all have their own methods and opinions. In this muddle, efficient work processes are often impossible.

According to a McKinsey study, construction products around the world exceed their budget by an average of 80%. People on site are actually only working 30% of the time. The rest of the day they are waiting for materials, or looking for something or somebody. A further tenth of their actual working time is spent either pulling down something they have already built or repairing it. So it comes as no surprise that the industry is probably the only one in the whole world in which productivity has been declining since 1994.

But it would be wrong to imagine that automation and digitisation have totally passed construction sites by. Building information modelling (BIM) creates 3-D plans that include all the information about a facility. There are also driverless building machines and partially automated concrete spreaders, and 3-D printers can produce rare components on site. Drones or small satellites are used to supply remote, dangerous or inaccessible sites. Logistics platforms plan delivery times and schedule the various skilled workers, showing in real time where each lorry is, where the materials are, and when the carpenters will arrive.

But these are all one-off solutions. Efficient supply chains, as long used successfully in the car industry, are still out of reach on a building site. The US construction industry came was above only agriculture in the digitisation index of the McKinsey Global Institute. And yet no other industry produces so much data, although 95% of it is deleted.

This is where Rhomberg steps in. Before the first trowel of mortar is stirred, Cree puts up the walls in cyberspace. “We create a digital twin of our building. In sectors such as mechanical engineering that has long been standard practice,” he says. In construction that can only work when every component is given an IP address, where information on price, weight, manufacturer or supplier are lodged. The building site becomes an internet platform.

“At first our idea was no more than to build in a more modern and sustainable way,” says Rhomberg. What was lacking was a convincing business model. “The cloud-based platform is allowing that to emerge more and more clearly.” Rhomberg says he was looking for something that could be multiplied. So why not just supply the knowhow to allow anybody to build a high-rise anywhere?

So far, he has been using the commercial platform BIMobject, where Cree uses its own cloud to enable its customers to access more than 4m individual parts. According to Rhomberg, about 500,000 users around the world are currently working with this service. As a next step, he is working on a platform of his own, to serve as a meeting point, a cluster of knowledge and a marketplace. All the Cree projects so far built or planned are intended to be accessible to all users. It helps planners to form virtual teams or firms in order to realise major projects, and developers can look for specialists. Or they can enter the data of the building they want to construct – and the platform will suggest plans, parts and prefabricated modules. It even generates a cost projection, right down to the last component.

A local timber construction firm can produce sections from this information, and module builders on the spot can assemble them. Architects, too, can help themselves to the data for their plans. Cree charges 5% of turnover for every project realised via the platform. The aim is to make it possible to find ready-to-build projects, making an expensive planning process unnecessary. Cree can already supply about 80% of the data needed for a building permit in any particular country. The remaining 20% comes from the local partner. “And the partner then feeds his knowhow back into the platform. We make that a condition. In this way a tremendous amount of knowledge comes back to the platform and is no longer lost.”

At present Cree is setting up a separate “room” for the planning authorities. They have greater trust in each other than in the data of the companies. “Here, they can exchange information. That also benefits us in applying for permits, if the officials can call on colleagues who have already implemented such projects.”

Sections being produced at Sohm HolzBautechnik

The need for speed

Cree’s competition with its parent company is a little mischievous, Rhomberg admits. “Cree naturally also benefits from Rhomberg’s competence in construction or building permits procedures.” But he is quite serious about wanting to create the world’s biggest building firm. “Today, even the big concerns only account for a tiny share of the world market. Why should it not be possible to do better than that with a repeatable system?”

Rhomberg is so firmly convinced that it is possible that he has now bought out his former partners and co-founders. He is a man in a hurry, with plans for new projects in Singapore and North America. There is a reason for his hurry: others are now showing an interest in the construction industry. Rhomberg needs to be well out in front, because he might soon find himself facing far bigger competitors. “Most construction firms work with SAP [a major European business software corporation]. And with our platform even a software firm like that could build high-rises.”

According to Rhomberg, the German industrial conglomerate Bosch has a building technology division and is also looking at the construction sector. He isn’t surprised. “Hardly any other industry has automated production as efficiently as the automobile industry and manages to make so many different models from the same few platforms,” says Rhomberg. Building might follow the same route. If prefab takes off, the automobile industry would be a true partner. “All the more so,” says Rhomberg “because the way things are looking, there may be plenty of free capacity available there soon.”

Perhaps skyscrapers will then start rolling off the assembly lines.

Hubert Rhomberg is not the only one rethinking construction. Others are thinking along similar lines:

The scientist

Alexander Rieck, at the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering (IAO) in Stuttgart, Germany, is researching future construction techniques as part of the innovation network Fucon 4.0. He is also a partner at the Laboratory for Visionary Architecture (Lava): b1.de/Fraunhofer_Fucon

"At the IAO one of the things we have been researching for 20 years is virtual reality. This technology established itself very quickly in automobile and aircraft construction and shipbuilding, but it was not really used in the construction industry. Innovations only gain ground slowly in construction because it is almost impossible to implement new procedures in such a fragmented and inflexible market.

In fact, the industry is heading towards a point when it will longer function. At the moment, quality is still guaranteed by skilled workers. But the supply of trained people is running short. And the problem of finding enough young people is becoming critical. In a few years, firms will hardly be able to find anyone prepared to start work at 5am in all weathers.

The different laws, autonomous processes and the multiplicity of trades is another problem: creating integrated chains is almost impossible. There is also a lack of major partners to press ahead with changes. Independent tradesmen and small planning offices find it difficult to acquire knowledge and launch complex new processes.

But digitisation will transform the construction sector within a few years. I can sense a new upbeat spirit. For example, we are collaborating with a research project in Saudi Arabia. Working with German firms, it is planned to set up a digital factory for the automated production of buildings to meet the annual demand for about 600,000 apartments. Several futuristic megacities are being planned in the Middle East. We simply cannot build them the old way any longer.”

The planner

Fabian Scheurer is an IT specialist and co-founder of Design-to-Production, based on Lake Zurich. It is a digital planning office for particularly complex and challenging projects that are difficult to display clearly on two-dimensional plans, such as so-called free forms such as the Pompidou Centre in Metz: b1.de/Pompidou_Metz

"Computers are still far too often regarded as a substitute for the drawing board. The key step – making all the data for a construction project machine-readable and processing it without the need for human interpretation – has yet to be taken. If this were to succeed, we could solve many of today's problems by means of digital systems.

Our customers are sick and tired of the problems on the building site. It is wet, cold and dirty, so not the right place to produce good quality. That is why we are focusing on digital prefabrication.

The industry can already call on superb machines, like extremely accurate CNC [computer numerical control] milling, but we do not have the data to optimise these machines. It is absurd how much information we lose in the construction process.

Another problem is that architects submit designs in competition but they cannot have any contact with the construction firms that calculate a tender. The lowest bidder wins. That is absurd, because particularly for complex projects where there is often no standard solution available, contact between the planners and the actual builders would be of fundamental importance.

That is why we are often too late in responding to public invitations to tender. We begin with digitisation and detailed specification. On the usual 1:50 plan there is a tolerance of half a centimetre, but on our digital models we work with precision down to a tenth of a millimetre. That meets the production tolerance of the CNC machines and the demands of the final assembly.

This delayed digitisation of the planning is a huge challenge because as a rule we get too little information or false information. To this day with the Centre Pompidou in Metz we do not know who developed the 3-D model that our planning was based on. It was displayed in a very simple fashion, with straight lines only, but in reality curved wooden parts were required. So we often start off by dumping the input and doing it all over again. That is terribly inefficient, but the quality of the input model is crucial to whether we can build on it in order to automate the detailing and production of thousands of individual components and connection details.”

The developer

Achim Nagel is an architect and founder of Primus Developments, a project development firm in Hamburg. He also tries to tread new paths in construction, such as the Woodie project in Hamburg, student accommodation made entirely out of prefabricated timber sections: b1.de/QuartierWoodie; b1.de/woodieHH

“I like looking for projects where I can experiment. We recently completed a project with 371 modular prefabricated rooms for students, each including a bathroom, cupboard, bed and kitchenette. The units were supplied by an Austrian timber constructor.

With this project we invested more time in the planning, which took a year longer than usual. But then we assembled all 371 units in three months. After only nine months the building was ready for the students to move in – with conventional building techniques that would have taken about two years.

I have now lost interest in conventional building sites. Instead, we are looking to see how we could prefabricate bigger accommodation units. Attractive 90 sq m [970 sq ft] apartments can be put together using three modules.

I think of all the time and trouble we still face once the building is finished, because of damp, mould or construction errors. We finish building something and then we spend half as much time again repairing what was botched during construction. But the industry is like a giant oil tanker. Sometimes I feel frustrated because everything takes so long. It's a pity that a lot of people quickly develop misgivings about new ideas and decide not to touch them. But things are changing, partly because of what people need. When students who have lived in our hostel move to another town, they ask us if there is a hostel with our concept there, too."

The woodworker

Katharina Lehmann is the president of the administrative board of Blumer-Lehmann, Swiss specialists in free-formed wooden support and casing structures, as used for the new Swatch headquarters in Biel/Bienne in Switzerland: b1.de/BlumerLehmann

"We are currently digitising the processes involved in working and building with timber. Perhaps the material itself can be digitised in future. For example, the specifications of its properties could be altered with biochemical processes. Or we could print a wooden bench with a 3-D printer.

The timber construction industry has been using IT-supported planning processes and prefabrication for 20 years. Developers have realised it provides a high degree of security with regard to planning, costs and meeting deadlines. In our experience, we need information from other trades far earlier than conventional builders. That is because in timber construction the cavity for an electric socket or space for wiring has to be planned right from the outset. That often leads to us taking over the control of the process and coordination of the planning. By now about a third of our jobs involve planning or project management. The conventional building industry still uses sequential planning, which tends to be belated and uncoordinated. A lot of the work is only decided on site. And then errors creep in. We could build a lot more with wood. In Switzerland at present only about half of the potential timber in the forests is being exploited.”