Focus on the customer!

Heidelberg went from the world’s market leader in printing presses to near bankruptcy, but saved itself just in time. A salutary tale from German industry.

It was pretty hairy for a while. So hairy, in fact, that almost no one believed the company had a future. Heidelberger Druckmaschinen had been in desperate straits for some time. With the steady advance of digitalisation, printing firms had been buying fewer machines; and no sooner had the decline bottomed out than the financial crisis came along. As its customers went bankrupt and the company itself slipped ever deeper into the red, Heidelberg was staring into the abyss. In 2009, it applied for a state bailout, coming away with €850m (then £720m).

This was nothing less than the collapse of a standard bearer for German mechanical engineering. Founded as a maker of bells, fire extinguishers and steam engines 167 years ago, Heidelberg later started producing printing presses for books. In the early 1960s, it sold its first offset press. This remains the most widely used printing process and Heidelberg became the market leader in it, growing into a multinational with more than 24,000 employees around the world and generating an annual turnover of more than €5bn.

Then, in 2008, came the financial crisis. It felt genuinely apocalyptic. The company management opted for radical restructuring, cutting thousands of jobs and imposing short-time working on the rest. Moreover, the company started to develop a business area it had neglected since the 1990s: services. For decades, makers of home and office printers had been earning more money from selling ink and toner than from selling their machines, and Heidelberg realised this model had huge sales potential for manufacturers of industrial printing presses, too. Customers only invest in new equipment every few years – and not at all when times are hard – but they need paper, ink, and lacquer on a weekly basis.

And, as Heidelberg discovered, they can also benefit from the advice of a consultancy. “Many customers think the only thing that can be improved is the machine. After a while, it becomes clear that the real problem is the person using it or the purchasing department,” explains Oliver Demus, a customer adviser at Heidelberg. “That is why we help printing companies to improve their business as a whole so they can increase their profitability.”

If the customer is doing well, the supplier earns more on the machines and materials it supplies. Industries have been selling services linked to their products for decades. Yet Heidelberg was behind the curve and it wasn’t until 2010 that services got their own business division.

From then on, the strategy was to shift from being just a supplier to being a full-service partner. Up until then, Heidelberg had measured itself mainly on the performance of its machines: “We were strongly driven by technical considerations. It was all ‘higher, faster, further’,” say members of staff, recalling the race to print ever more sheets per second, to speed up switching between jobs. It was about being at the head of the pack, about setting the pace for the competition. What no one was asking was whether the customers actually benefited.

Heidelberg still builds high-performance printing presses. One of its most recent efforts, Primefire 106, stands in its research and development centre opposite Heidelberg’s main railway station. Several metres long, this digital hi-tech giant has its own walkway but is controlled by the click of a mouse. It prints packaging; able to handle the smallest of runs and a bewildering number of variants, putting more than 12bn droplets of ink in seven colours on to a single sheet of paper. The price tag is €3m (£2.6m). One customer is already using it and has ordered a second machine. Heidelberg developed the new press in just two and a half years – a new company record.

Digitalisation paves the way for new services

New techniques such as digital printing play an important role in Heidelberg’s R&D. Worldwide, the overall market for printed products is considered stable: in the emerging economies, the total volume is still going up, and although online media are taking market share from classic print media such as newspapers, magazines, and brochures in developed countries, packaging and labels are growing markedly. Yet Heidelberg’s competitors are also building digital printing presses and, so far, few customers are investing in the expensive new technology. While Heidelberg remains the market leader in offset printing, with a market share of 45%, there is no growth left in this segment now that improving performance allows one new machine to do the work of two older ones.

“That is why we are entering into new business areas,” says Rainer Hundsdörfer, Heidelberg’s chief executive. “In our case, the greatest potential for growth is in providing services to our customers.” Aged 60 and appointed last November, Hundsdörfer is one the board members. He is new to the printing industry but has spent all his working life in the machine-building sector. In his view, his role is to be “the most senior salesperson in the company”. His goal is for Heidelberg to be achieving at least half of its turnover from services in future, reducing the share derived from machine sales to a third.

This target is in no way unrealistic: at €8bn, demand for printing materials is more than three times the size of the global market for offset printing presses - and at present, Heidelberg has just 5% of it. That leaves plenty of potential for the company’s problem-solving consultants, who are working to a new motto: “We listen. We inspire. We deliver.” Sounds sensible; what else would you expect? For Heidelberg, however, it’s a steep learning curve. “We were somewhat arrogant,” Gerold Linzbach, Hundsdörfer’s predecessor, conceded last year in an interview with the financial markets daily Börsen-Zeitung: “We had to learn to listen to our customers.”

And it would appear that Heidelberg is learning fast. Its consultancy offer has grown considerably in recent years, as Jürgen Hofmann, the owner of a medium-sized printing company in Emmendingen near Freiburg, south-west Germany, explains. “They’ve got experts who are wholly specialised on printing companies,” he enthuses, “and they’ve been our sole suppliers for decades.” As such, there are benefits for both parties.

By 2013, five years after the start of the financial crisis, the Heidelberg corporation was back in the black. It now has 11,500 members of staff, 4,000 of whom are at the headquarters in Wiesloch-Walldorf near Heidelberg, with another 1,000 in the research and development centre in town. The company’s most recent annual turnover figures showed earnings of €2.5bn, with international business contributing 85%; services around the core printing press product are now responsible for almost as much revenue as sales of new machines. Since 2000, the proportion of total turnover from services has more or less tripled.

And Hundsdörfer sees even more opportunities in an industry currently undergoing transformation: even small printing companies are now being affected by digitalisation, so Heidelberg will have to digitalise its services, too.

“The press has stopped working again – looks like the same problem as last week. What’s going on?” It’s the emergency call that makers of printing presses get on a regular basis. A classic offset press has several thousand sensors, and as soon as something goes wrong, the machine alerts its operators. “That will soon be a thing of the past,” says Tom Oelsner, head of sales management. He and his team have developed an app that allows clients to identify problems and report them to Heidelberg before the machine comes to a standstill. A technician can then log into the dashboard and resolve the issue – remotely, where possible.

Still selling machines: the showroom at the headquarters in Wiesloch, near Heidelberg

Amazon is the example

The digital assistant doesn’t stop there, though. It also compares the performance of the client’s press with anonymised data from other printing companies’ machines, providing advice on how to improve output as well as offers on printing materials. It’s a holistic service concept driven by data - or, as you might call it, the Amazon model. Heidelberg already has all the information it needs, because it started connecting machines it sold to its service system 12 years ago. It is now a matter of using the data collected in a systematic way.

Demus and his client consultant colleagues are already developing their next product. Instead of selling printing companies materials, replacement parts and services, Heidelberg will start offering them the option of paying per sheet of paper printed – a subscription model as practised by photocopier manufacturers. “Our clients won’t have to finance the press up front, making their business easier to plan,” says Demus. For Hundsdörfer, the advantage of the model for Heidelberg is clear: “If we are present across all client operations, then we are no longer dependent on just selling machines. It’s a whole new business model – and one that will enable the digital transformation.”

While the “Made in Germany” label continues to enable manufacturers to charge a premium, the general view in the sector is that this is the right way forward. A publication by the German Mechanical Engineering Industry Association (VDMA) talks about networking products and processes as an excellent opportunity “to secure the competitive edge of German mechanical engineering in the long term” against a backdrop of the international competition making great strides. “Machine builders can differentiate themselves from their competitors by offering everything their clients need to operate profitably,” emphasises Markus Heering, head of the VDMA paper and print division, and this means that “manufacturers of machinery need to adapt to the new structures in their client organisations.”

In its study of digital business models and trends in the mechanical engineering sector, the consultancy Wieselhuber & Partner also concluded that developing new digital services and business models would become more important than improving machine performance. Increasingly, it said, customers expected packaged solutions and contributions to greater efficiency in their production processes: “Today’s machine-building firm needs to remain in control of the customer interface, focus on its own core competencies, and integrate intelligent partners in order to offer operators added value.”

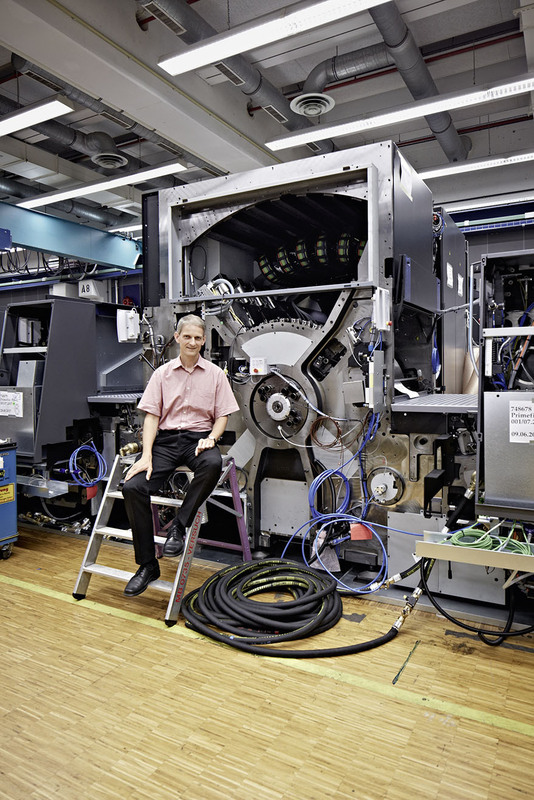

Here’s how it works: machines being demonstrated in the Wiesloch factory.

Out of the comfort zone

Heidelberg is now cooperating with manufacturers across the world to provide its clients with everything they need, even buying in the chemicals, lacquering systems, and glues used in print processing that it does not produce itself. Some products are developed by Heidelberg but made by partner companies: ink for digital printing, for instance, is essential for the quality of the result and so commands a good margin. Acquisitions are another way Heidelberg brings new competencies into its organisation, the most recent being a small software firm.

Something else that is different now – and that would have been utterly unthinkable in the halcyon days – is close customer contact without an immediate sales motivation. Demus and his team made the first step, each of them spending a week with a printing company and investigating that firm’s processes. Now customers are involved in the product development stage: when Oelsner’s department started designing the new service app, they met print professionals, asking them about their problems and noting their ideas and wish lists; they then followed up the visits every three weeks to show the progress that had been made and receive feedback for further development.

As simple as this process may sound, it took some getting used to for many in the company. “Customer-centrics, agile development, testing prototypes and then going back to the drawing board if it doesn’t work? All new for Heidelberg,” says Oelsner. “Sometimes, in the canteen, colleagues would come up to me and say: ‘So you mean we don’t yet have a full, 150-page spec’ and you’re already starting?’ Sometimes, you simply have to force people out of their comfort zone and make them take risks,” he concludes, “and that means learning to deal with growing pains.”

There has been growth in the organisation, too. Members of staff who were previously in touch by email or on the intranet, if at all, are now working side by side. Software for manufacturing processes is no longer programmed in the IT team’s open-plan offices, but down on the workshop floor. Felix Blome, a developer, and Ralf Keller, an assembly planner, are both sitting at Keller’s workstation. “I was involved at a far earlier stage and was able to tell the developers what can be built – and what can’t,” says Keller. Blome, too, stresses the benefits of the new way of working: “I can implement changes straight away and then we test them together; if necessary, I can make other modifications immediately.”

These considerations are what is behind the planned move of the R&D centre from its current location in the middle of Heidelberg out to the factory at Wiesloch. “It took some people a while to warm to it,” admits Hundsdörfer. “But it will help us generate new ideas, make us more agile and more competitive. We will also be reducing the number of management layers. During the crisis, we needed clear direction and strong discipline, but now we’re switching to giving people more freedom and more responsibility so they can implement their ideas.”

Heidelberg is at the beginning of a change of company culture. In times gone by, the company liked to showboat at industry expos, spending – some say – eight-figure sums on trade fair stands annually. The crisis years have left behind a far more modest organisation. Last year, Heidelberg held a stay-at-home expo and invited its clients to the factory. The new boss has a reputation as being easy-going. Yet after the harsh cutbacks, many employees remain cautious. “We’ve got to challenge our people – and enthuse them too,” says Hundsdörfer. “That is our core task.”

The current premium model, the Primefire press with Hans Butterfaß, head of digital printing development.

Goodbye perfectionism

Hundsdörfer is counting on communication to do the job, which is why he meets his third and fourth-tier managers once a week and regularly drops in to the supervisors’ meetings. He also uses an intranet blog to write about management decisions and responds to questions and criticisms from employees.

“If our client market is changing,” reasons Hundsdörfer, “then we as manufacturers have to change, too. That, though, is where the difficulty lies. It’s all very well producing technical innovation at high speed, but changing an organisation takes a long time.” On his first day at work in Heidelberg, Hundsdörfer made a speech: “There is no one big lever that I, as chairman of the board, can find and pull to get results. It is piecemeal, step-by-step work – and it’s a job that never ends. Successful companies never relax. They keep moving, keep the tension up – and keep fighting every day.”

Hundsdörfer wants the organisation to lose its perfectionist streak, which he regards as leading to paralysis. Instead of tinkering endlessly, people should just get started. “If we can’t do it one way, we’ll do it another,” he says, “I’m pretty flexible on the ‘how’ of the matter. Startups have two or three ideas and are prepared to fail on all counts. We have hundreds of ideas, but if we avoid trying any of them for fear of failure, we’ll end up not doing anything at all.”