Bosch

Driving change

Which way to the internet? Bosch is transforming itself for a digital car future – despite roadworks along the way

• Volkmar Denner, chief executive of the German electronics giant Bosch, arrived for the recent Bosch ConnectedWorld conference in Berlin in a digitally pimped S-class Mercedes driven by his counterpart at Daimler, Dieter Zetsche. The two men got out of the car, Denner activated the autopilot via his smartphone, and the luxury saloon glided off by itself to the VIP car park.

Automated valet parking (AVP) is the robot equivalent of the professional service offered by luxury hotels. Drivers with AVP no longer need to descend into smelly, draughty underground car parks; they just leave their car at the entrance. The system makes the best use of limited parking spaces as with no doors to open, spaces that used to fit three cars can now accommodate four. Car park dents will be a ding of the past, too, as the technology becomes more widely adopted. However, as with many other aspects of self-drive cars, the question is when?

When innovation depends on networks, the rules of the game are changed: commercial success is no longer a question of exclusivity and unique features but of cooperating in clever ways. For Daimler to be able to offer its customers AVP, it needs a partner like Bosch. The world’s largest automotive supplier can draw on know-how gained in automating factories and offices, as well as the “internet of things”. For AVP to work, car parks need transmitters to guide vehicles into spaces scarcely wider than themselves. However, that’s no good to Daimler unless Bosch manages to convince other carmakers to get on board. Car park operators will only refit their premises if there are enough self-parking cars in use. The concept relies on the network effect: only if everyone acts in concert does everyone stand to benefit. If they do not, it becomes a bad investment. And yet AVP is just the first step along the road to interactive cars.

How autonomous?

The idea that people will soon stop buying private cars because they will be able to call up a share car whenever they need one still seems a distant dream. Yet Germany’s first driverless car could in fact be a Mercedes robot taxi. For this project too, Daimler is relying on Bosch. It is a sign of pragmatism that the partners are not developing a private car or a robot Car2Go (another Daimler subsidiary) for their autonomous driving debut, but a kind of hail shared taxi. This type of service can easily be piloted in particular neighbourhoods where equipment can be set up. Traffic lights could, for example, send a wireless signal to a car’s onboard computer.

The developers of self-driving cars would have an easier time if they knew more about where the vehicles were being used – the turmoil of an Asian megacity makes different demands on the technology than a Californian highway or a snowy forest backroad in Bavaria.

A vehicle can move around autonomously using digital maps, sensors, cameras, radar and lidar (light detection and ranging) systems. But this does not work everywhere or all the time. Matters are expected to improve if information can be added from an “internet of things” cloud, local infrastructure or other road users. Bosch is working intensively on this type of concept; it has already developed a system that allows motorbikes to wirelessly alert approaching vehicles – also non-autonomous ones – to their presence.

The obstacles along the path from driving to being driven are substantial. Network solutions such as AVP require cooperation from many parties on many levels but people are also suspicious of allowing artificial intelligence to make decisions on their behalf. It will be exciting to see, therefore, how people react to the first robot taxis and how well those work. Only once that is known will Bosch and its customers in the automotive industry be able to gauge whether there is actually a market for cars without a steering wheel and pedals or just for conventional models with extended driver-assistance functions.

Who pays and can it pay?

The car industry’s traditional business model was simple: new features were initially limited to luxury vehicles, becoming standard issue as manufacturing costs dropped. This no longer works when new technologies need a connected world. To prevent motorbike accidents, it is not enough for Yamaha, Honda or BMW to install Bosch’s warning transmitters in their bikes; the signal will remain unheard unless cars have the corresponding receivers on board.

So it would make sense to install the technology quickly as a standard feature, ideally with several manufacturers collaborating over a common standard. However, inventors do not want to hand over their work for free and carmakers are not keen to increase production costs by adding features that cannot be recovered easily from sales.

Ultimately, the charm of digital automotive progress lies, not least, in a style of driving that might be described as social. Many new developments are based on working together on the road: altruism rather than egotism. Bosch engineers are suggesting that connected cars could use their cameras and sensors to scan roadsides for parking spaces and upload that information to the cloud. This would help the owners of older cars, too, and reduce the number of cars crawling around in search of parking spots.

The first people to buy new cars with such altruistic features would not benefit, however. As cars in Germany average 18 years before they are scrapped, the initial buyers would have sold them long before there are enough connected vehicles on the roads.

In fact, it is Bosch that is investing up front. For years, the company has been ploughing back almost 10% of turnover into research and development. At times, it is so far ahead of its times that it is hard to make out a suitable business model for some of the ideas.

The narrow meshes of the fifth-generation mobile networks, for example, will theoretically allow all road users to be connected to the infrastructure. But no one knows yet how much of the hype will become reality. It might be financially worthwhile for network operators to provide blanket 5G coverage – if car drivers are willing to show solidarity and pay for this. Either way, Bosch is getting ready for the new wireless standard.

Collision course?

One of the biggest problems for Bosch’s customers in the automotive industry is the need to lower their fleets’ carbon emissions. This is why Volkswagen, Audi, BMW and Mercedes-Benz are investing in electric models. Nevertheless, their brands continue to be defined by extravagant combustion engines. They have little experience with electrically powered vehicles.

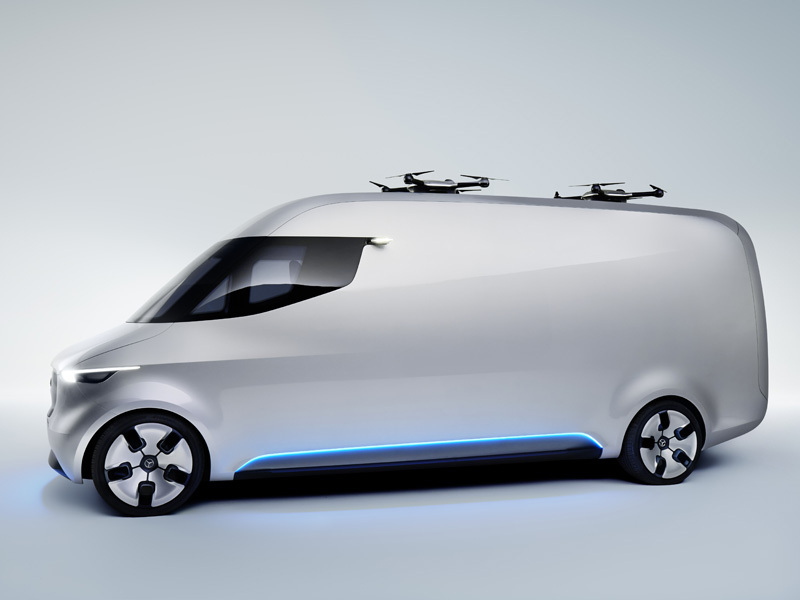

Bosch, on the other hand, does. The company’s motors not only power e-bikes and e-scooters, but also the StreetScooter, a postal delivery van used by Deutsche Post DHL. Like its rival car-parts maker ZF in Friedrichshafen, in southern Germany, Bosch has developed an entire drive unit or e-axle for battery-powered cars – lowering the obstacles to market entry for new competitors of the established carmakers. All it takes to put a new vehicle on the road is a body, an interior and to design the chassis with a protective cage for the battery. The rest can be purchased straight from Bosch.

Günther Schuh is a professor at the technical university RWTH Aachen and on the board of the carmaker e.Go Mobile in Aachen. He does not think much of the idea of major carmakers reinventing the wheel, so to speak, when it comes to electric drives. “Under normal circumstances, someone entering the market laterally like this would never tackle the issue,” says Schuh. The managing boards are trying to keep the creation of value in-house, he says, but that does not necessarily make sense from a strategic point of view.

If Bosch supplies motors to a small-scale manufacturer such as e.Go Mobile, which is expecting to launch its affordable Life electric car soon, that will not hurt the big players. However, Bosch is also doing business with Chinese carmakers and this could put it and other suppliers such as ZF on a collision course with their best customers in the long run.

If customers were to switch to electric cars quickly and in large numbers, Denner would have a problem. Some 227,000 of the Bosch workforce are employed in the automotive sector, which currently thrives on combustion engines. Like the carmakers themselves, major suppliers need time to get to grips with the transition to the electric age.

The market forecasts used by Denner at Bosch’s Schillerhöhe headquarters in Gerlingen, outside Stuttgart, suggest they have time. For now, at least, the scandal over diesel emissions is more of a problem than a potential run on electrical outlets. About 50,000 jobs depend on the diesel or compression-ignition engine alone – one in eight of the company’s 400,000 jobs around the world.

The question is not whether, with the help of Bosch, carmakers can build diesel engines able to meet emissions standards but rather whether they can win back the trust of car buyers – and whether clean diesels will be able to compete with petrol engines on cost. While Volkswagen is still promoting low-carbon turbocharged direct injection (TDI) diesels, Toyota has now decided to stop producing diesel cars in Europe altogether.

Meanwhile, electric car enthusiasts have had their hopes dampened by the technical challenges and need for scale in developing lithium batteries. The properties of these rechargeable cells are decisive for the competitiveness of electric cars, but how quickly can the ion tank provide the necessary power, and for how long? How long will it take to charge? And how many years will a battery last?

At the IAA international motor show in Germany in 2015, Denner still sounded very optimistic. A new type of electrochemical cell, which Bosch had been working on with the Japanese manufacturer GS Yuasa since 2013, was expected to produce twice as much energy per unit volume for half the price by 2020.

In order to stay in the game for the next stage of development, Bosch purchased the Californian startup Seeo. It seemed as though e-cars with a range of more than 300km might become affordable for the average family. The German corporation looked all set to get involved in making high-tech cells. But the technology-driven euphoria soon gave way to economic realism. According to Denner’s calculations, a German or European producer would have to secure 20% of the global market to hold its own against Asian manufacturers. The production capacity needed would cost €20bn (£17.5bn) – a lot of money, even for a profitable multinational like Bosch, though manageable for a consortium of carmakers. However an alliance of this kind, which the German government and the European Commission would have welcomed, never came about.

Despite announcing that they were going to launch an entire series of electric cars, including some with long ranges, the managing boards of BMW, Daimler and Volkswagen would not commit to investing in their own battery-cell production. They were content with building small test factories, to acquire know-how, but they continued to buy from South Korea, China and Japan.

At the end of February, Bosch followed, announcing it was withdrawing from the once-promising market. The company now intends to buy electrochemical cells on the international market and confine itself to assembling them into ready-to-install battery packs. This decision is based on an in-house projection indicating that in two years just one car in 33 (passenger cars and light commercial vehicles) would be powered entirely by electricity; by 2025 the number was projected to reach one in 10 and by 2030 one in five. The batteries in hybrid vehicles, which are forecast to achieve only 6% of the market, will be of little consequence. This means that the combustion engine will remain the dominant method of propulsion for a long time to come.

Was it right to get out of electrochemical cell production? That depends on your perspective. With the high cost of energy there, it was always unlikely that production would take place in Germany. Bosch’s market scenario may contrast with the planned electric offensive of the carmakers, but Stefan Bratzel, an automotive expert at the business polytechnic in Bergisch Gladbach, in western Germany, does not believe there will be a big boom in electric vehicles. “In our most optimistic scenario, 15% to 25% of newly licensed vehicles in 2025 will be electrically powered. That means 75% to 85% of all new vehicles will still be driving around with combustion engines.”

One factor that is difficult to predict is the rollout of charging facilities. Deutsche Telekom intends to convert thousands of junction boxes into charging stations; while the German utilities company EnBW and others are making street lamps fitted with sockets for charging cars (see brandeins 08/2017 ‘And again, from the top’). The idea is that anyone driving around town only really needs to recharge enough electricity for a few kilometres while they are parked, and will never run their battery flat. This would allow connected city runabouts such as Schuh’s e.Go Life to establish themselves at least as a second car – in which case Bosch, too, would benefit – as a supplier of battery packs.

When people talk about the “future of mobility”, they are quick to theorise that owning a car will become unimportant and that this would be bad for manufacturers. The concepts for connected driving that Bosch is working on with its partners are based on the assumption that cities will still face the problem of excessive road traffic. Some experts even joke that there will be more congestion if people are able to send out an unmanned car to run their errands for them.

Bosch is therefore working on intermodal services featuring more than one means of transport: if all the different means are interconnected – from private cars, buses and railways, to car-pools – a computer could work out the ideal combination. In Berlin and several other big cities, Bosch is already renting out electrical scooters and it has purchased the US lift-sharing startup Splitting Fares – better known as SPLT – which organises employee car-pooling for employers using the cloud and an app.

Bratzel is interested in who will dominate the value-added chain in the future and who will control the customer interface: carmakers, suppliers or IT companies such as Google, Apple and China’s Alibaba? He is not worried about Bosch: “Big automotive suppliers with strengths in the areas of the future will be among the winners of the transformation.” Denner is not one to bandy around superlatives. This makes it all the more dramatic when the 61-year-old boss of the largest limited company in German industry says Bosch is undergoing the “biggest transformation of its company history”.

What other people call digitalisation goes by the name of “connectivity” on Schillerhöhe, according to Bernd Heinrichs, the chief digital officer. Connectivity stands for the ability to form networks, both technically and socially. Bosch’s image of itself is being transformed, he says, as the company systematically adds internet connectivity to all its electronics. “The traditional automotive supplier is developing into a connected services player.” The internet of things opens the door to mobility services and much more. A Bosch app can, for example, tell workers whether all their tools are in their van and where they are stored. Although Bosch still makes its profit with physical products, it already employs 25,000 people in software development – as many as the entire full-time workforce of Facebook.

This reorientation is a gradual process. The internet of things has been on the agenda for 10 years, and for almost six of them Denner has been balancing getting the company’s product portfolio fit for the future while streamlining Bosch in an effort to acquire more “agility”. This buzzword from the field of software project management now refers to the battle against bureaucracy, divisional egotism, sluggish business procedures and perfectionist engineering that does not take customers into consideration. In practice, this means that employees from different departments are trained in “design thinking” so they can specifically develop new products from the users’ point of view in interdisciplinary teams. The fields of construction, design, product management and marketing are merging, though not yet throughout the entire company.

In order to improve communications between the different lines of business, Bosch has for three years now backed “working out loud” (WOL), a peer-coaching method refined by an American, John Stepper. For three months, four to five people from different departments meet once a week for an hour, online or in person, to learn from each other. By now, more than 1,000 employees have taken part in such groups. For a corporation with 400,000 employees that wants to become a learning company, this is just the start.

Every new project that Bosch tackles is supposed to avoid the so-called silo problem, right from the beginning – its internet of things development centre in Berlin, for example, shares a modern building with the corporate subsidiary Software Innovations. The company attracts talents for the growing industry of connectivity by the same methods used in the IT industry, with events such as the Connected World hackathon. Here, external participants and Bosch employees from all over the world meet and compete to produce the best internet of things idea using Bosch products.

Word seems to have got around that the one-time industrial corporation has now become a major IT player: the first hackathon, four years ago, was attended by 30 people – this year, more than 700 came.